Anchors in the storm

A social identity perspective on group membership and elite athlete transition

Unpublished masters research project

Tom Fright

School of Health, Education, Policing & Sciences, University of Staffordshire, Stoke-on-Trent, United Kingdom

Acknowledgements

My sincere thanks to the retired athletes who shared their time and (often challenging) experiences so openly to make this study possible. I am grateful to my supervisor, Karla Drew, for her thoughtful guidance, constructive feedback and acting as a critical friend who challenged my thinking during analysis.

Abstract

Retirement from elite sport is a psychologically demanding transition in which identity processes play a central role. Drawing on the Social Identity Model of Identity Change (SIMIC), this qualitative study explored how recently retired elite athletes navigated identity loss, continuity and gain. Five athletes (individual and team sports; Australia, New Zealand, UK) completed semi‑structured interviews and a Social Identity Mapping (SIM) exercise used as a qualitative elicitation/structuring tool. Reflexive thematic analysis generated two overarching themes: (1) balancing and integrating identities and (2) active sense‑making and identity repurposing, highlighting “identity docking” and the micro‑processes by which athletes flex and reorganise identities around sources of meaning and control. Findings advance SIMIC by illustrating that identity continuity can function as a time‑limited protective “bubble” that buys space for subsequent identity gain, rather than being sufficient in its own right. Second, athletes who had practised shifting between roles could up‑/down‑regulate salient identities as sport receded; I term this ‘identity flex’. I refine SIMIC by privileging identity quality/compatibility, proposing continuity‑as‑bubble, and foregrounding identity elasticity as a potentially trainable skill. Practically, periodic SIM‑style conversations at key inflection points and identity‑leadership that legitimises dual commitments may aid transition. These theory‑building claims require longitudinal, multi‑actor tests. These insights extend SIMIC’s application in sport and refine targets for transition support.

Keywords

Elite sport retirement, athletic identity, social identity model of identity change, identity management

Introduction

Our disposable gladiators

This emotional distress reported by athletes retiring from their sporting career was articulated by Kahn (1972), who popularised the sporting proverb ‘an athlete dies twice’ in reference to the impact an athlete’s retirement has. Indeed, retirement from sport has previously been studied through the lens of thanatology, framing retirement as a form of social death (Rosenberg, 1982), with Kubler-Ross (1969) suggesting athletes go through stages similar to those facing literal death. In the 50 years since, the issue of managing the process of athletic retirement has been amplified by the professionalisation of sport, where athletes often pursue full-time athletic careers from a young age.

Retirement from elite sport and beginning a new life is often referred to as a transition (Park et al., 2013). Three predominant categories of sporting transitions have been proposed: normative (expected), non-normative (unexpected), and quasi-normative (expected for a particular category of athletes; Stambulova et al., 2020).

The period is increasingly recognised as a period of psychological vulnerability. Research has shown that athletes navigate this transition more successfully if they are more educated (e.g., attended university), have maintained a dual career (Stambulova & Wylleman, 2019), and have planned for and engaged in the transition voluntarily (Kuettel et al., 2017; Park et al., 2013). However, for many athletes, maintaining a dual career is not possible due to the demands their sport places on them. In addition, approximately 50% of athletes will face involuntary retirement (Lyons et al., 2018). Research has shown that this category of athlete (who retire involuntarily due to injury, deselection, or non-renewal of contracts) reports increased risk of emotional distress, identity loss, and social disconnection (Park et al., 2013).

Unlike previous generations who balanced sport with education or work, many modern athletes have fewer opportunities or incentives to develop broader identities. As a result, when retirement comes, particularly unexpectedly, athletes may lack the psychological resources to adapt successfully (Alfermann et al., 2004). These data suggest that the most efficient research on athlete transitions centres on variables that are, to some extent, within an athlete’s control, as opposed to structured retirement plans that athletes, particularly those early into their career, may struggle to engage with (Lavallee, 2018).

Significant factors on transition quality

The transition from athlete to non-athlete invokes a reconfiguration of a self and social identity (Haslam et al., 2024). Athletic identity – the degree to which athletes define themselves through sport (Brewer et al., 2000) – is a key part of a person’s identity and also a key factor influencing transition quality.

Elite athletes often cultivate a strong and singular identity built around sport. While a strong athletic identity is positively associated with performance (Ronkainen et al., 2016), it can also create vulnerability at the point of retirement, especially if athletes lack other roles or group affiliations to support their identity (Park et al., 2013). Consequently, a singular identity has been linked to poorer transition outcomes, particularly when retirement is unplanned and the person is less ‘ready’ for the psychological demands of transition (Alfermann et al., 2004). This is often attributed to identity foreclosure, where athletes commit early and exclusively to the athlete role, without developing alternative roles or exploring life beyond sport (Lally, 2007; Alfermann et al., 2004). Those with foreclosed athletic identities are particularly at risk of experiencing identity loss, emotional upheaval, and social isolation (Park et al., 2013).

Many factors have been shown to have a significant impact on transition (Park et al., 2012), including their level of education and prior engagement in retirement planning. Building on this, recent research suggests that social support impacts transition. Athletes have highlighted former teammates and coaches as being a positive influence on their ability to better manage their transition (Park et al., 2012). Conversely, athletes have reported a lack of organisational support as a factor in making them feel used and abandoned as they struggled with their transition (Brown & Potrac, 2009).

Outside of formal organisations and governing bodies, family members and friends often play a crucial role in transition by providing work opportunities, career assistance, and emotional support (Park et al., 2013). In particular, romantic partners have been recognised as important sources of emotional comfort and often as a primary source of support (Gilmore, 2008; Sinclair & Orlick, 1993). However, in both instances, there is variability in the quality of the support that athletes receive. Athletes who have experienced difficult transitions have reported a lack of support from organisations, or that their family and friends did not fully understand what they were going through. As a result, athletes found it difficult to turn to them for support or see value in the support that was offered (Gilmore, 2008). Therefore, it is important to gain a better understanding of how these interactions can provide a positive influence on athletes transitioning from elite sport.

A framework for success

Athlete retirement and transition was initially studied through the lens of thanatology and gerontology (Burgess, 1960) as more of a one-time event. However, Schlossberg’s Model of Transition (1981, 2004) was the first to adopt a multi-dimensional model that viewed transition as a process. Taylor and Ogilvie’s (1994) conceptual model of adaptation to career transition aligned with Schlossberg’s theory but importantly provided an athlete-specific model and was the first to highlight social identity as an important variable.

The Social Identity Approach, which combines social identity theory and self-categorisation theory, explains when our group self becomes the lens through which we think and act, and what that means for cognition and behaviour (Tajfel & Turner, 1979; Turner et al., 1987). Building on this, the Social Identity Approach to Health (SIAH) argues that because group life is the main way people access belonging and shared meaning, social identities can promote health as readily as they can undermine it.

Crucially, it is not nominal membership but the strength of identification that matters for health-relevant outcomes (Haslam et al., 2018). When people strongly identify with valued groups, they can access psychosocial resources, such as belonging, meaning, perceived control, esteem, efficacy, and support, that reliably underpin adjustment and health across contexts (see Rees et al., 2022, for a detailed discussion).

Applied to athlete retirement, this implies that transition quality depends less on how many affiliations athletes have. Instead, it depends more on how strongly and meaningfully they identify with them, and on the fit between past and new identities. This logic is operationalised in SIMIC, which emphasises preserving identity continuity and cultivating identity gain through compatible, meaningful group memberships.

There is also considerable evidence that social factors play an important role in helping people navigate life transitions more generally (i.e., outside sport). For instance, research has shown that people’s health following retirement from the workforce is typically greater (a) if they possess high-quality and supportive relationships and, of particular relevance to the present study, (b) if they possess more social group memberships (Haslam et al., 2018; Stevens et al., 2021).

Research has pointed to the importance of social groups for performance (Rees et al., 2015; Slater et al., 2020). White et al. (2021) found that the resilience of Royal Air Force (i.e., military) personnel was supported by belonging to a greater number of “positive” groups, while other research has pointed to the importance of people’s group memberships being compatible with each other (Iyer et al., 2009). In a sporting context, there is empirical evidence that an athlete’s social group memberships can facilitate improved heart rate recovery (Jones & Jetten, 2011) and persistence in sporting tasks (Green et al., 2018). Moreover, if one's sense of belonging to a single group has this capacity, arguably belonging to multiple social groups is especially beneficial because this increases a person's access to more health-promoting resources (Haslam et al., 2018).

One emerging framework that has attempted to explain these concepts is Social Identity Model of Identity Change (SIMIC). SIMIC proposes that people cope better with life transitions when they can maintain existing group memberships or gain new ones—providing continuity, belonging, and identity reinforcement (Haslam et al., 2020). This is important in relation to elite athletes, who often sacrifice other group memberships in pursuit of excellence (Beamon, 2012). This may leave retiring athletes without the identity continuity or support structures needed to navigate this transition smoothly.

The SIMIC framework offers a lens to understand and potentially buffer these effects. It suggests that the ability to maintain pre-existing group memberships or gain new ones helps protect well-being during major life changes (Haslam et al., 2020), with further research suggesting that these effects may be particularly prominent in the (relatively) early phase of the post-transition period (Rees et al., 2022).

Although SIMIC has been applied in contexts such as illness, relocation, and ageing, it remains underexplored in elite sport, despite athletes being particularly vulnerable to identity loss during transition (Stevens et al., 2024). Moreover, it remains unclear whether having a high number of groups is protective or whether it is the quality and emotional significance of those groups that matters more (Stevens et al., 2024) and the role that the quality of the athlete's group plays within this context (Rees et al., 2022). This study addresses that gap directly, using Social Identity Mapping to assess both the structure and emotional significance of group memberships, followed by qualitative interviews to explore athletes’ lived experiences.

By targeting recently retired athletes, including those who exited sport involuntarily, this research aims to generate timely, relevant insights. The findings may inform future identity-based interventions, athlete development programs, and practical tools for enhancing transition readiness. It is anticipated that the findings will be relevant to sport psychologists, coaches, and organisations supporting athlete transition. It also offers broader theoretical value by testing and extending SIMIC in a new and applied context. The researcher’s personal connection to the topic will be acknowledged through ongoing reflexivity to ensure the integrity of the research process.

Method

Methodology and design

This study adopts a critical realist ontology and an interpretivist epistemology (Danermark et al., 2002; Fletcher, 2017). I assume athletes’ transitions involve real events and structures (e.g., injury, deselection, organisational policies), yet my access to these realities is mediated by meaning, context and language; themes are therefore constructed through analysis rather than “discovered” (Braun & Clarke, 2019; Fletcher, 2017). The logic of inquiry is abductive: moving iteratively between participants’ accounts and concepts from SIMIC and the wider social identity approach. Theory was used as a sensitising lens to refine, rather than predetermine, interpretation (Danermark et al., 2002; Haslam et al., 2024).

The researcher was treated as an active analytic instrument, with reflexive journaling and critical-friend discussions used to surface how prior sporting experience shaped questions and inferences (Braun & Clarke, 2019; Finlay, 2002). Social Identity Mapping was employed as a qualitative elicitation/structuring device to organise talk about identity networks; any simple ratings attached to maps functioned as prompts for discussion rather than psychometric data (Haslam et al., 2024). The aim is analytic transferability of insights to similar contexts, not statistical generalisation (Braun & Clarke, 2019).

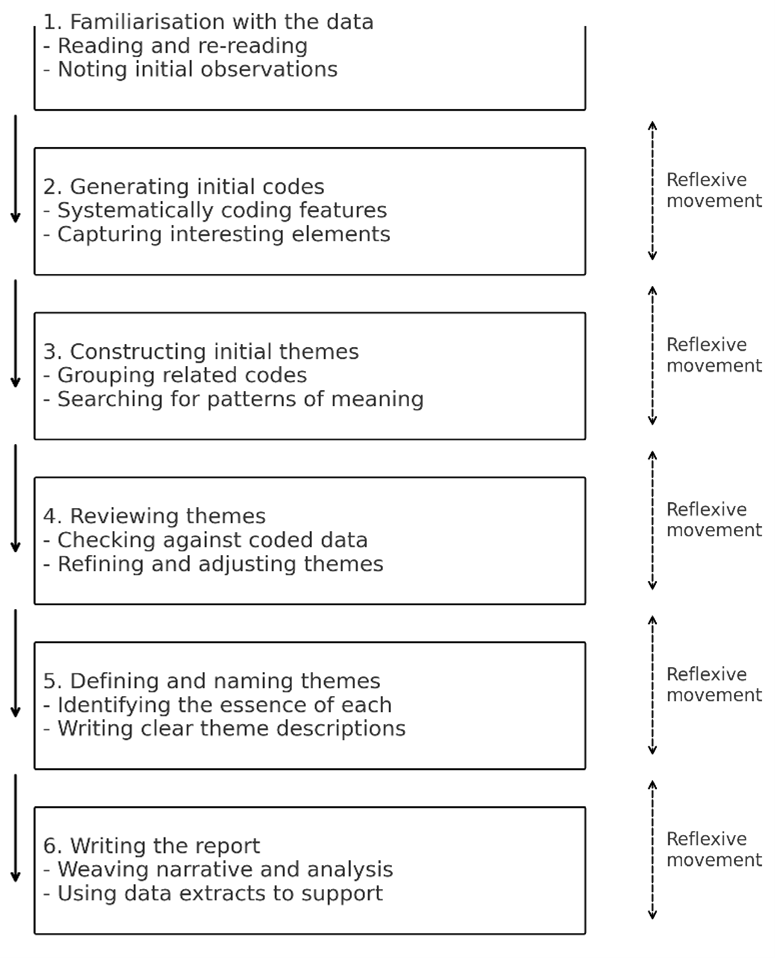

A reflexive thematic analysis (rTA) was conducted following Braun and Clarke’s (2019) six-phase framework (Figure 1). This method was chosen due to its flexibility and accessibility for novice researchers, and its capacity to generate rich, nuanced insights to inform the broader patterns that can be generalised across individuals (Park et al., 2013).

Figure 1. Braun and Clarke’s (2019) six-step guide to rTA (researcher’s interpretation)

Unlike Haslam et al. (2024), I did not brief participants on identity theory to avoid leading responses. To mitigate the risk of overly personal (non‑identity) emphasis (Lally, 2007), closing questions asked what would help other athletes and invited any identity‑relevant issues not yet covered. This preserved conversational freedom while ensuring sufficient identity coverage.

Positionality

The authorship team comprised myself, a 35-year-old post-graduate student, under the direction of my supervisor. Both of us were able to draw on our own experiences of transitioning from an elite athletic career, while my supervisor was able to draw on significant qualitative research experience in athlete transition pathways.

Participants

Five participants were recruited for the study, all of whom had retired within the last ten years (Table 1). These athletes competed at Olympic and/or World Championship levels (or the junior equivalent), engaging professionally in their sport. Participants fell between competitive and successful elite, as defined by Swann et al. (2015), in that they competed at the highest level of their sport and either had limited success or won events and/or medals, respectively. All athletes had benefitted financially from their sporting careers, although not all were financially profitable from their sporting careers. Their athletic careers spanned between three to ten years, and they had been retired between one and ten years. While Park et al. (2013) highlighted one to five years as the period of greatest adjustments, Knights et al.’s (2016) systematic review showed that relevant results could be achieved with athletes who had been retired for more than ten years.

Table 1. Participant demographic and sport characteristics

While it must be acknowledged that the number of participants may not be enough, it was felt that the data provided in the five interviews was rich enough to provide a meaningful body for rTA analysis. In addition, the sample size is in line with previous research using qualitative semi-structured interviews (e.g., Gorman & Blackwood, 2024), where small but information-rich samples were used to explore identity and adaptation processes in depth. As this research was exploratory in nature from the outset, it is intended that any themes will serve to support existing research or offer a starting point for future research, rather than the relatively small sample size counting against findings in this research. Participants were identified via existing professional networks and through snowball sampling, whereby the researcher accessed new participants through contact information provided by existing participants (Noy, 2008). This method is particularly useful when accessing hard-to-reach or specialised populations, such as retired elite athletes (Atkinson & Flint, 2001).

All participants were assigned a pseudonym at the point of transcription (e.g., “Participant KQ”). This pseudonym was used throughout all transcripts, analysis, and reporting to ensure confidentiality. Any document linking real names to pseudonyms was stored separately in a secure, password-protected file and permanently deleted once transcription accuracy had been confirmed. Interviews were recorded (with consent) and transcribed using Otter.ai, with Teams used as a backup in case of technology issues. Transcripts were anonymised and returned to participants for accuracy checks.

Given the anticipated difficulties, the participant pool was kept as open as possible in terms of sport type, sex, and transition pathway, while still meeting the core inclusion criteria. This flexibility was necessary to ensure sufficient participation and to maximise the diversity of experiences captured in the study, although the researcher acknowledges that this may have introduced additional variability that may have been detrimental to the analysis. No inducements or payments were offered for participation.

Data collection

Ethical approval was granted by the University of Staffordshire. Data were collected (June–August 2025) via (a) a Word‑based Social Identity Mapping (SIM) exercise and (b) a 30–60‑minute semi‑structured interview using Teams (M45 SD12). SIM captured the structure/quality of current group memberships and is validated as a person‑centred mapping tool r = 0.37 to 0.84; Cruwys et al., 2016), including online use (Bentley et al., 2020). Participants were sent the SIM document to complete prior to the interview and offered the choice of drawing a map of social groups they belonged to, with themselves at the centre, or articulating these groups in a table format. For each named group, participants rated (1–5) (i) belonging/support and (ii) identity importance, then brought the SIM to the interview (map or table format).

The data was used to support the semi-structured interviews. Participants were asked to reflect on (a) their sporting career, how they got into sport and what led to their retirement, (b) their experience of transition, (c) their identity and how, if at all, it changed during transition and afterwards, (d) how athletes could be better supported in the future. Interviews took place individually over Teams.

Data coding and analysis

A ‘Big Q’ qualitative approach was taken, meaning that themes were not treated as emerging from the data, but as actively constructed through researcher interpretation and reflexive engagement (Finlay, 2021). Reflexivity was treated as central to this process, and the researcher’s subjectivity was acknowledged as a resource, not a bias to be eliminated (Braun & Clarke, 2021). Other approaches were considered but deemed less appropriate. Grounded theory was not suitable, as the aim was not to generate new theory. Discourse analysis was also ruled out due to its focus on language construction and its complexity (Jorgensen & Phillips, 2002), which did not align with the author’s novice status or the intent of the research. In contrast, rTA offered both structure and flexibility, making it accessible while supporting creativity and interpretation—qualities well suited to an interpretivist stance (Braun & Clarke, 2021).

An abductive approach was adopted for the qualitative analysis, combining existing theoretical concepts from SIMIC with the exploration of new insights emerging from athlete narratives and identity mapping. This abductive approach allowed for an open engagement with the data while still supporting links to relevant literature.

The coding was conducted by myself, with my supervisor available as a critical friend. The transcript was read multiple times before being coded using NVivo. Coding began at a semantic level and moved toward latent interpretation. I used parent-child structuring to organise codes and identify broader patterns. Annotating the transcript helped surface early interpretations and prompted questions I returned to later. Theme development involved grouping codes, refining meaning, and using theory to move from descriptive patterns to more analytical insights. I acknowledge that my own experience of a relatively difficult transition from being an athlete shaped how I interpreted the data. This design is justified by the complexity of the research topic, the limited prior research in this area, and the rich insights that can be gleaned from rTA.

Rigour

To support rigour in my research, I was guided by recommendations from Tracy’s (2010) “big-tent” criteria, while rTA-specific guidance from Braun and Clarke (2019). Rich rigour was pursued via a focused aim, information-rich sampling, and prolonged, iterative engagement documented in an audit trail of dated memos, codebook snapshots, and theme development. Sincerity/reflexivity was supported by journaling that tracked how my background shaped prompts and interpretive moves (Finlay, 2002). For credibility, I privileged thick description and multivocality, evidencing claims with participant language (Geertz, 1973; Tracy, 2010), while deliberately avoiding procedural checks that sit poorly with rTA (e.g., intercoder reliability; theme “validation” by participants). Participants were invited only to verify transcript accuracy. Resonance/transferability were enhanced by situating extracts in context and drawing out practical implications that are likely to “travel” to similar settings (Lincoln & Guba, 1982). Judgements about sample sufficiency followed information power rather than saturation (Malterud et al., 2016). Ethical practice was addressed procedurally (consent, confidentiality) and relationally (care during/after interviews). Taken together, these strategies privilege depth, transparency, and reflexive judgement over consensus metrics, consistent with an interpretive, critical-realist stance.

Reflexivity

I recognise that my own involuntary retirement shaped what I noticed and asked of participants. This near‑insider status was both risk and asset: shared vocabulary and experience appeared to build rapport and elicit candid, information‑rich accounts, while journaling and ongoing critical reflexivity helped guard against over‑identification (Dwyer & Buckle, 2009; Berger, 2015; Malterud et al., 2016). I used rTA in line with Braun & Clarke (2019), drawing on published exemplars (e.g., Trainor et al., 2020) and SIMIC as a sensitising framework to move from description to analysis.

Results and discussion

Two themes capture how identity processes shaped athletes’ exits: (1) Balancing and integrating identities and (2) Social networks and transition resources. Both themes are interpreted through SIMIC, focusing on how continuity, gain, and compatibility enable adjustment.

Table 2. Themes

Theme 1: Balancing and Integrating Identities

Participants contrasted a foreclosed, singular athletic self with a more diversified self. Theme 1 shows how these different identity management strategies shaped psychological adjustment at exit.

5.1.1 Identity foreclosure complicates transition experiences

Participants who voiced a more singular identity around their sport faced significant psychological challenges during retirement. Participant NQ, who specialised from childhood and relocated for coaching, described an early, narrow athletic identity,

"When I was around 12 or 13, I moved back and forth between New Zealand and Australia... living with my coaches during school holidays because coaching was better in Australia... I transitioned fully to living in Australia, finished high school remotely, and trained full-time."

Her athletic identity developed largely in isolation from broader social networks, restricting exposure to alternative identities or group memberships. Consequently, retirement (prompted by an overuse injury) triggered substantial identity disruption and emotional distress, "Transition was awful... I got dropped immediately. My funding and sponsorships stopped. I had no psychological support. It was extremely difficult."

Consistent with SIMIC, this illustrates low identity continuity and delayed identity gain, combined with low control over retirement, contributed to distress (Haslam et al., 2024). Similar dynamics are reported elsewhere, with Brown et al. (2018) highlighting variable quality and availability of support from sporting organisations as a significant variable in transition quality. This situates NQ’s account in an all too familiar structural pattern rather than as an isolated grievance.

KK also foreclosed early, “I started around five... it was mainly rugby league”, yet benefitted from retiring voluntarily and securing a role at his club, "I was lucky moving straight from retirement to still being around footy... It's important to be in that team environment, even though it's different." This stabilised his identity transition by providing a new group that was compatible with his athletic identity (Iyer, 2009). However, he noted struggling initially, “I didn't really have a defined role”. This sense of continuity without purpose caused frustration, illustrating how compatibility can buffer shock but is no guarantee of restoring meaning, providing a time-limited bubble. For KK, this threatened to reduce the meaning the club had to his identity, which could have escalated if left unresolved. Fortunately, KK had a newborn son at the same time, which stepped in to fill this void, providing an opportunity for identity gain, “while I sort of lost purpose at work, like off, off the field, like at home, it was, it was a good it was a good space just to get away from it.”

KK’s comparatively smoother transition underscores that athletes with foreclosed identities can navigate retirement effectively, but they are at a greater risk. For example, KK transitioned to a group that was compatible but lacked the same purpose and therefore meaning (Haslam et al., 2021). While this void was filled by KK’s role as a new father, this is not a strategy that is available or possible to all. Indeed, such conditions are often contingent on external factors beyond athletes' control, highlighting identity foreclosure as an inherent risk factor for difficult transitions.

5.1.2 Multiple identities facilitate smoother transitions

Athletes who actively balanced multiple identities reported steadier adjustments. KI demonstrated notable maturity in deliberately prioritising her academic goals at a pivotal career moment, “I stopped swimming because my coach wanted me to swim more, and I just wanted to finish school.” This decision showed early willingness to down‑regulate the athletic self in service of another valued identity (Haslam et al., 2021). This flexibility, strongly influenced by parental guidance, provided crucial psychological resilience during her eventual transition from sport. KQ similarly maintained a meaningful academic identity, partly through parental expectation, “I always did my academics as well, and that was quite drilled into me from my parents…I still really wanted to do well academically.”

KQ's ongoing academic pursuits (it should be noted that all participants of relevant age achieved a at least bachelor’s degree before retiring) and a desire to proactively maintain multiple identities (“the [university] course I was on, I said I ran like, no one give a shit that I did…it was good”) provided psychological stability by offering a secure, alternative source of identity and self-worth beyond her athletic performance. It was evident that this approach helped buffer her frequent and significant injuries, “I'd probably have…six months out of injury, and then I'd come back…for like, nine months, and then I'd have a substantial injury”, and subsequently insulated her from the significant identity loss commonly associated with athletic retirement (Lally, 2007). She explicitly linked her positive transition outcomes to the psychological skills developed through balancing these identities, “I think those skills really helped during the transition. You build those skills and draw on them at critical moments.”

These cases sharpen two points. First, identity diversification here was less about strategic identity construction and more about family norms and educational scaffolding that normalised having more than one important group. Second, participants emphasised quality and meaning (a few identities that really matter) rather than sheer quantity (see Appendix C for an example social identity map). That aligns with SIMIC’s compatibility and meaning mechanisms and qualifies ‘more groups’ claims by centring compatibility, meaning, and phase‑sensitive effects observed elsewhere.

These patterns also intersect with early specialisation. In sports such as figure skating, pathways often channel children into intensive, exclusive programmes from a young age. Such conditions are repeatedly linked with overuse injury and constrained social development, and which can narrow identity options outside sport (Cattle et al., 2023). In that context, the capacity to sustain non‑sport memberships (e.g., school, work, family) looks less like a ‘nice to have’ and more like protective scaffolding that keeps identity resources available as circumstances change. In practice, that places a premium on structures that keep alternative groups genuinely open. Parents who normalise multiple commitments, schools and employers that are flexible, and federations that avoid policies which implicitly penalise diversification (Cattle et al., 2023) are all factors that appear likely to increase transition quality.

Interestingly, the data suggest it is not only having multiple groups that matters, but being able to flex identity—down‑regulating the athlete self when needed and up‑regulating compatible alternatives to preserve meaning and control. For example, KI’s choice to prioritise school at a pivotal point, while KQ’s ability to lean into academics during repeated injuries and also go all-in on running when required, both exemplify this dynamic regulation.

Currently, this concept of regulating identity on a daily, weekly, and monthly basis appears to be lacking within SIMIC. To solve this, I propose that a micro‑process of identity flex helps explain why some athletes transition well, even with a limited quantity of groups. It appears that what counts is the skilled, timely shift between valued, compatible identities (consistent with SIMIC’s compatibility logic). Methodologically, SIM is well‑suited to explore this micro‑process, helping to clarify how continuity and gain jointly operate, a relationship still underspecified in recent qualitative SIMIC work (Haslam et al., 2024). Conceptually, elasticity also dovetails with emerging evidence that, for retired athletes, cognitive flexibility is a significant predictor of happiness and wellbeing (Davies et al., 2024), even if such effects are weaker while athletes are still competing. Finally, given that group‑membership effects can be most visible in the early phase after a change (Rees et al., 2022), training how to flex may be as important as what to add or maintain.

Taken together, the practical takeaway is modest but actionable: rather than simply ‘collect more groups’, help athletes practise shifting salience between a small number of valued, compatible identities, while ensuring the ecology around them (family, school, federation) keeps those alternatives viable.

5.2 Theme 2: Social Networks and Transition Resources

Across participants, social relationships mattered less as generic support and more as identity resources: ties that preserved continuity when sport fell away, and pathways that enabled identity gain. Three patterns stood out: (a) one or two “anchor” ties that did heavy lifting during the messy middle; (b) purposeful (or fortuitous) re‑anchoring into groups that matched the feel and functions of athletic identity; and (c) ruptures—organisational and relational—that complicated both. This extends SIMIC by foregrounding which ties/groups matter and why (compatibility and meaning), not simply how many.

5.2.1 Anchor ties: when one person is worth five groups

The importance of a partner/spouse as a source of support has emerged as a significant factor in athlete transition (Gilmore, 2008; Sinclair & Orlick, 1993). For KQ, her husband functioned as a stabilising identity anchor,

“And my husband, you know, he’s obviously very supportive in everything, and just wanted to see me happy.”

“I think if I didn’t have my husband… I think that would be so difficult.”

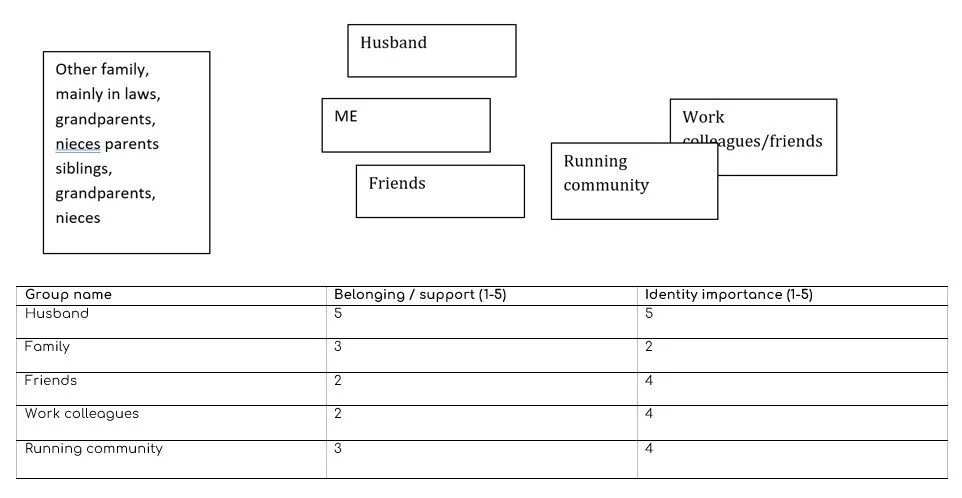

Her SIM map mirrors this: ‘Husband’ was rated the most important tie, with other circles (family, friends, colleagues, running community) contributing identity in different ways but with noticeably weaker belonging.

Figure 3. KQ SIM

As used here, SIM is a qualitative elicitation/structuring tool to surface identity resources; it’s not a psychometric outcome. See Appendix C for the map and prompt wording.

Two nuances follow. First, belonging does not equal identity. In KQ’s map, some groups were low on felt belonging yet still did identity work. For example, work colleagues conferred competence/esteem even when attachment was thin. That nuance is underplayed in much transition literature that either counts memberships or treats “support” monolithically.

Second, the unit is not always a group. A dyadic tie (spouse/partner) outperformed whole categories. That sits awkwardly with strong claims that group‑based ties trump interpersonal ones (e.g., group memberships predicting health more than one‑to‑one ties; Stevens et al., 2021), and points to boundary conditions in that dyads can sometimes concentrate identity resources more efficiently than diffuse groups when meaning is high and responsiveness is immediate.

This emphasis on meaning and compatibility aligns with SIMIC’s continuity/gain pathways but invites a refinement: rather than a ‘more‑the‑merrier’ rule‑of‑thumb, the protective mechanism appears to be fit (does the group carry the same psychological functions the athlete valued in sport, such as purpose, competence feedback, shared narratives, daily structure). One implication of why KQ valued her partner so strongly is that KQ met her partner doing her PhD research and therefore there was a meaningful shared identity between them. In contrast, KI’s partner was removed from both work and sport, meaning that, while his support was still valued, on its own it was not sufficient, with KI noting that she needed the support of someone that had been through a similar experience. This underscores a useful distinction: closeness is necessary, but shared identity is what often makes support effective (Brown et al., 2018; Park et al., 2012). This helps explain why athletes can find it difficult to turn to friends and family for support or see value in any support offered by this group (Gilmore, 2008).

While all participants identified at least one consistent supportive person across their careers and into retirement, NQ’s experience highlighted a nuance. To support her skating, her mum gave up her teaching career to homeschool and manage training, "So not only did we have to deal with, like, me exiting. But my mum also was like, I don't know what to do now… so yeah, both of us were like, oh God". This illustrates how NQ had foreclosed around the athlete role and, to a degree, her mum around the “skating‑parent” role. When sport ended, both were forced into transition simultaneously. This co‑transition may have narrowed available identity continuity and temporarily reduced her mum’s capacity to buffer NQ’s adjustment, even as she clearly remained a supportive figure for NQ.

These findings reinforce SIMIC’s emphasis on the compatibility and emotional significance of social group memberships (Iyer et al., 2009; Haslam et al., 2021). For athletes, retaining or establishing close, compatible relationships, particularly those rooted in shared experience, appears to be a vital resource for maintaining identity continuity and psychological wellbeing during the post-sport transition. Therefore, encouraging athletes to actively maintain at least one emotionally reliable relationship and one identity‑congruent relationship before retirement may create redundancy in the support system. This avoids over‑reliance on a single tie, protects wellbeing during setbacks, and increases the chance that athletes convert adaptive capacities into concrete post‑sport roles. For practitioners, this suggests building structured touchpoints with partners, alongside facilitated peer connections (e.g., alumni networks, mentor pairings, or small peer circles) that remain active into the first year post‑retirement.

In the next sub‑theme, I examine how broader groups can fill the void left by sport and provide the daily rhythms, roles, and recognition that consolidate a new, sustainable identity.

5.2.2 Re‑anchoring: docking into groups that ‘feel like sport’

Several participants described identity gain by moving into groups that reproduced elements of their athletic identity. IX’s account of joining a golf club was a classic example of re‑anchoring: social routine, graded challenge, visible progress, and a community of practice, “if I didn't have golf, the transition would have been way harder”.

KI highlighted the value of opt‑in peer spaces, “made by athletes, for athletes with people that are going through things at the same time”, while also noting that timing mattered, as not everyone would be receptive to the same support at the same time. This temporal gating of support is not explicit in SIMIC, although there is alignment with Rees et al.’s (2022) research showing that new group memberships were most pronounced soon after transition and attenuated over time, consistent with a phase‑sensitive process rather than a uniform dose‑response.

Therefore, while alumni groups and informal peer networks can serve as identity ‘docks’, they rarely provide such a neat bridge as governing bodies expect, with KI, KQ and KK all noting support available that either they or their peers had failed to engage with. Moreover, these data provide further comment to the debate between the value of received versus perceived support (see Brown et al., 2018, for wider debate). The results from this study clearly align with Rees and Freeman’s (2007) findings that received support is most valued, but this can hardly be considered conclusive evidence. One question that arises is whether athletes struggle to engage with governing body support due to the conflict that places on their identity transition (i.e., if you are trying to distance yourself with your old athletic identity, it may be distressing to engage with a group so tightly linked to that old identity).

Critically, the participants’ experiences sharpen SIMIC’s identity gain pathway (Iyer et al., 2009; Haslam et al., 2018) in that athletes did not just add groups, they sought (or stumbled into) functionally compatible groups that afford mastery, shared narratives, and role clarity. Contributing to the SIMIC debate on quantity versus quality of groups (Stevens et al., 2021), this helps explain why IX’s golf club, and subsequent business running a golf performance centre worked, why KK’s initial staff role only partly worked (see below), and why generic support pathways or community groups can fall flat even if they tick the ‘more memberships’ box.

5.2.3 Rupture and ambivalence: when structures withdraw and relationships flip

NQ’s story illustrates how organisational withdrawal can precipitate identity loss. Her deselection/injury resulted in lost funding, lost status, and thin welfare provision, “I got dropped immediately…funding and sponsorships stopped…I had no psychological support”. She later described how some relationships that felt like family, such as the coach she lived with, were contingent on performance and proximity; once she left, contact and care diminished. This echoes prior work on variability in organisational support and athletes’ feelings of being used and abandoned at exit (Brown & Potrac, 2009; Brown et al., 2018).

In addition, the relationship with her family was also strained due to the fact that her mother had foreclosed her identity around being a “skating‑parent” role. When sport ended, both were forced into transition simultaneously. "So not only did we have to deal with, like, me exiting. But my mum also was like, I don't know what to do now… so yeah, both of us were like, oh God." This co‑transition may have narrowed available identity continuity and temporarily reduced her mum’s capacity to buffer NQ’s adjustment, as her mother’s identity was also changing at a time NQ needed some form of continuity.

KK’s path shows a more benign version of rupture. Early on, he labelled the move from player to staff as, “shifting from the driver’s seat to the passenger seat”, with a temporary loss of purpose despite the badge and building remaining the same. That looks like continuity, but the functions that gave his athletic identity meaning (clear role, unambiguous feedback, public recognition) were not initially present. Fatherhood incidentally filled that purpose gap, before a role change in the organisation (from strength and conditioning coach to pathways coach) led to him finding his purpose again.

This provides an important contribution to furthering SIMIC, with Haslam et al. (2024) stating they were still unsure of the relationship between continuity and gain pathways. KK’s case suggests continuity served as a time‑limited scaffold, maintaining belonging and predictability in the club environment, while identity gain (being responsible for developing junior players) provided renewed meaning and role clarity that his initial coaching position lacked. Without continuity, he believed adjustment would have been harder, “moving into a different environment…away from footy…would be really challenging”. Yet continuity alone was insufficient to restore purpose.

Given the exploratory nature of this current study, it is suggested that further research explores a scaffolded dual‑pathway process in which compatible continuity preserves core identity resources, thereby creating space for gain to emerge and ultimately dominate adjustment once the new identity attains sufficient centrality. This interpretation dovetails with SIMIC’s emphasis on compatibility and with longitudinal evidence that group‑membership effects are time‑sensitive early in transitions.

Limitations

This study offers depth rather than breadth. First, the sample was small (n = 5) and recruited via professional networks and snowballing, which likely favoured athletes willing to discuss transition; transferability, not statistical generalisation, was the aim. Second, data are retrospective and thus shaped by memory and current positioning; notably, one participant (NQ) narrated acute loss and organisational withdrawal long after the event, which aids insight but invites recall bias. Third, although SIM was used productively to structure talk about identity networks, these were of varying quality; I therefore treated SIM indices as prompts rather than outcomes, limiting triangulation with quantitative indicators. Fourth, I deliberately avoided pre‑interview grounding in identity theory (in contrast to Haslam et al., 2024), which reduced demand characteristics but may also have lowered the density of identity‑specific language in some interviews. Fifth, sports and career stages varied (e.g., figure skating versus rugby league; voluntary versus involuntary retirement), increasing ecological range but also heterogeneity. Finally, the single‑researcher analysis within a rTA frame strengthens coherence but concentrates interpretive lenses; I mitigated this through explicit abductive use of SIMIC, a transparent codebook and use of a critical friend. One element that showed promise for future research is female‑specific constraints (e.g., fertility timing and body image/adjustment in retirement) that participants raised but which exceeded the present scope.

Conclusion

Across contrasting exits, adjustment hinged less on the sheer number of affiliations than on a small set of meaningful, compatible identities that could carry purpose and control beyond sport. In some instances, continuity with sport groups buffered the initial shock and created a time‑limited “bubble” in which new roles could be trialled, but continuity alone was rarely sufficient; sustainable adjustment depended on identity gain that restored meaning. ‘Identity flex’ was also observed among those with smoother exits, suggesting a micro‑process that complements SIMIC’s continuity and gain pathways. Practically, light‑touch SIM‑style conversations at natural inflection points (major injury, team change, retirement) and identity‑leadership practices that normalise dual commitments can surface compatibility gaps and prompt pre‑exit identity building. These are modest, evidence‑informed refinements – cultivate a few valued, compatible identities early so that, when transition comes, athletes have both ballast and room to grow.

References

Alfermann, D., Stambulova, N., & Zemaityte, A. (2004). Reactions to sport career termination: A cross‑national comparison of German, Lithuanian, and Russian athletes. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 5(1), 61–75

Atkinson, R., & Flint, J. (2001). Accessing hidden and hard‑to‑reach populations: Snowball research strategies. Social Research Update, 33.

Beamon, K. (2012). “I’m a baller”: Athletic identity foreclosure among African‑American former student‑athletes. Journal of African American Studies, 16(2), 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12111‑012‑9211‑8

Bentley, S. V., Cruwys, T., Haslam, S. A., Haslam, C., & Gunasekara, A. (2020). Social identity mapping online. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 118(2), 213–241. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000174

Berger, R. (2015). Now I see it, now I don’t: Researcher’s position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 15(2), 219–234.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. Sage.

Brewer, B. W., Van Raalte, J. L., & Petitpas, A. J. (2000). Self-identity issues in sport career transitions. In D. Lavallee & P. Wylleman (Eds.), Career transitions in sport: International perspectives (pp. 29-43). Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology.

Brown, G., & Potrac, P. (2009). “You’ve not made the grade, son”: Deselection and identity disruption in elite level youth football. Soccer & Society, 10(2), 143–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970802601613

Brown, C. J., Webb, T. L., Robinson, M. A., & Cotgreave, R. (2018). Athletes’ experiences of social support during their transition out of elite sport: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 36, 71–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.01.003

Burgess, E. (Ed.) (1960). Aging in western societies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Cattle, A., Mosher, A., Mazhar, A., & Baker, J. (2023). Early specialization and talent development in figure skating: Elite coaches’ perspectives. Current Issues in Sport Science, 8(1), Article 013. https://doi.org/10.36950/2023.1ciss013

Cruwys, T., Steffens, N. K., Haslam, S. A., Haslam, C., Jetten, J., & Dingle, G. A. (2016). Social Identity Mapping: A procedure for visual representation and assessment of subjective multiple group memberships. British Journal of Social Psychology, 55(4), 613-642. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550614543309

Davies, R. M., Knoll, M. A., & Kyranides, M. N. (2024). A moderated mediation analysis on the influence of social support and cognitive flexibility in predicting mental wellbeing in elite sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 70, 102560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2023.102560

Dwyer, S. C., & Buckle, J. L. (2009). The space between: On being an insider–outsider in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8(1), 54–63.

Finlay, L. (2002). “Outing” the researcher: The provenance, process, and practice of reflexivity. Qualitative Health Research, 12(4), 531–545. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973202129120052

Finlay, L. (2021). The reflexive journey: Mapping multiple reflexivities. Qualitative Research, 21(4), 491–508. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794120933590

Fletcher, A. J. (2017). Applying critical realism in qualitative research: methodology meets method. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 20(2), 181–194.

Gilmore, O. (2008). Leaving competitive sport: Scottish female athletes’ experiences of sport career transitions. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, University of Stirling, Scotland.

Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures. Basic Books.

Gorman, S., & Blackwood, L. (2025). Inside the football factory: Young players’ reflections on being released from elite academies. Sport, Education and Society, 30(3), 315–330. Advance online publication 2024. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2024.2367114

Green, J., Rees, T., Peters, K., Sarkar, M., & Haslam, S. A. (2018). Resolving not to quit: Evidence that salient group memberships increase resilience in a sensorimotor task. Frontiers in Psychology, 9:2579. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02579

Greenaway, K. H., Haslam, S. A., Cruwys, T., Branscombe, N. R., Ysseldyk, R., & Heldreth, C. (2015). From “we” to “me”: Group identification enhances perceived personal control with consequences for health and well‑being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(1), 53–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000019

Haslam, S. A., Jetten, J., Postmes, T., & Haslam, C. (2012). Social identity, health and well‑being: An emerging agenda for applied psychology. Applied Psychology, 61(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464‑0597.2011.00406.x

Haslam, C., Haslam, S. A., Jetten, J., Cruwys, T., & Steffens, N. K. (2021). Life change, social identity, and health. Annual Review of Psychology, 72, 635–661. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev‑psych‑060120‑111721

Haslam, C., McAulay, C., Cooper, D., Mertens, N., Coffee, P., Hartley, C., Young, T., La Rue, C. J., Haslam, S. A., Steffens, N. K., Cruwys, T., Bentley, S. V., Mallett, C. J., McGregor, M., Williams, D., & Fransen, K. (2024). “I’m more than my sport”: Exploring the dynamic processes of identity change in athletic retirement. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 73, 102640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2024.102640

Haslam, S. A., Fransen, K., & Boen, F. (2020). The new psychology of sport and exercise: The social identity approach. SAGE.

Haslam, S. A., Jetten, J., Cruwys, T., Dingle, G., & Haslam, C. (2018). The new psychology of health: Unlocking the social cure. Routledge.

Iyer, A., Jetten, J., Tsivrikos, D., Postmes, T., & Haslam, S. A. (2009). The more (and the more compatible) the merrier: Multiple group memberships and identity compatibility as predictors of adjustment after life transitions. British Journal of Social Psychology, 48(4), 707–733. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466608X397628

Jones, J. M., & Jetten, J. (2011). Recovering from strain and enduring pain: Multiple group memberships promote resilience in the face of physical challenges. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 2(3), 239–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550610386806

Jørgensen, M. W., & Phillips, L. (2002). Discourse analysis as theory and method. SAGE.

Kahn, R. (1972). The boys of summer. Harper & Row.

Knights, S., Sherry, E., & Ruddock‑Hudson, M. (2016). Investigating elite end‑of‑athletic‑career transition: A systematic review. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 28(3), 291–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2015.1128992

Kübler‑Ross, E. (1969). On death and dying. Macmillan.

Küttel, A., Boyle, E., & Schmid, J. (2017). Factors contributing to the quality of the transition out of elite sports in Swiss, Danish, and Polish athletes. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 29, 27–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2016.11.008

Lally, P. (2007). Identity and athletic retirement: A prospective study. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 8(1), 85–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2006.03.003

Lavallee, D. (2018). Engagement in sport career transition planning enhances performance. Journal of Loss and Trauma. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2018.1516916

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1982). Establishing dependability and confirmability in naturalistic evaluation. Educational Communication and Technology, 30(4), 233–252.

Lyons, D., Williams, L., van Gerven, N., Söderlind, A., & Herber, J. (2018). Transition from sport: A review of player association research into retired players. World Players Association, UNI Global Union.

Malterud, K., Siersma, V. D., & Guassora, A. D. (2016). Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1753–1760. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315617444

Park, S., Tod, D., & Lavallee, D. (2012). Exploring the retirement from sport decision‑making process: A prospective study from a self‑determination theory perspective. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 13(4), 444–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2012.02.003

Park, S., Lavallee, D., & Tod, D. (2013). Athletes’ career transition out of sport: A systematic review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 6(1), 22–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2012.687053

Rees, T., & Freeman, P. (2007). The effects of perceived and received support on self confidence. Journal of Sports Sciences, 25(9), 1057-1065. doi:10.1080/02640410600982279

Rees, T., Haslam, A., Coffee, P., & Lavallee, D. (2015). A social identity approach to sport psychology: Principles, practice, and prospects. Sports Medicine, 45(8), 1083-96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-015-0345-4

Rees, T., Green, J., Peters, K., Stevens, M., Haslam, S. A., James, W., & Timson, S. (2022). Multiple group memberships promote health and performance following pathway transitions in junior elite cricket. Psychology of Sport and Exercise. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2022.102159

Ronkainen, N. J., Kavoura, A., & Ryba, T. V. (2016). Narrative and discursive perspectives on athletic identity: Past, present, and future. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 27, 128–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2016.08.009

Rosenberg, E. (1982). Athletic retirement as social death: Concepts and perspectives. In N. Theberge & P. Donnelly (Eds.), Sport and the sociological imagination (pp. 245–258). Texas Christian University Press.

Schlossberg, N. K. (1981). A model for analyzing human adaptation to transition. The Counseling Psychologist, 9(2), 2–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/001100008100900202

Schlossberg, N. K. (2004). Counseling adults in transition (2nd ed.). Springer.

Sinclair, D. A., & Orlick, T. (1993). Positive transitions from high‑performance sport. The Sport Psychologist, 7(2), 138–150.

Slater, M. J., Thomas, W., & Evans, A. L. (2020). Teamwork and group performance. In S. A. Haslam, K. Fransen, & F. Boen (Eds.), The new psychology of sport and exercise: The social identity approach (pp. 75-94). Sage.

Stambulova, N. B., & Wylleman, P. (2019). Psychology of athletes’ dual careers and transitions: A developmental perspective across the lifespan. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.128

Stambulova, N. B., Ryba, T. V., & Henriksen, K. (2020). Career development and transitions of athletes: The ISSP position stand. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 18(6), 737–748. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2019.1695527

Stevens, M., Cruwys, T., Haslam, C., & Wang, V. (2021). Social group memberships, physical activity, and physical health following retirement: A six‐year follow‐up from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. British Journal of Health Psychology, 26(2), 505-524.

Stevens, M., Cruwys, T., Olive, L., & Rice, S. (2024). Understanding and improving athlete mental health: A social identity approach. Sports Medicine, 54(4), 837–853. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-023-01879-0

Swann, C., Moran, A., & Piggott, D. (2015). Defining elite athletes: Issues in the study of expert performance in sport psychology. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 16, 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.07.004

Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big‑tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(10), 837–851. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800410383121

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Brooks/Cole.

Taylor, J., & Ogilvie, B. C. (1994). A conceptual model of adaptation to retirement among athletes. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 6(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413209408406462

Trainor, L. R., & and Bundon, A. (2021). Developing the craft: reflexive accounts of doing reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 13(5), 705–726. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2020.1840423

Trainor, L. R., Crocker, P. R. E., Bundon, A., & Ferguson, L. (2020). The rebalancing act: Injured varsity women athletes’ experiences of global and sport psychological well-being. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 49, 101713.

Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D., & Wetherell, M. S. (1987). Rediscovering the social group: A self‑categorization theory. Blackwell.

White, C. A., Slater, M. J., Turner, M. J., & Barker, J. B. (2021). More positive group memberships are associated with greater resilience in Royal Air Force (RAF) personnel. British Journal of Social Psychology, 60(2), 400-428. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12385